Machines Do Not Speak English

Back in my freshman year of CS 101, there was one thing that genuinely baffled me while learning C. ‘Why can not I just run the code? Why do I have to go through this annoying ritual of Building and Compiling?’

With Python, I could just write a script, hit Enter, and boom—it worked. But with C (and later Java), there was always this friction. It felt like an unnecessary waiting room. At the time, I just shrugged it off as ‘syntax differences’. On exams, I memorized the standard answer: ‘C is a compiled language; Python is an interpreted language’. I got the A, but I didn’t get the point.

It wasn’t until I started managing backend servers handling massive traffic in production that I realized this wasn’t just trivia. This simple difference regarding ‘Build vs Compile’ is the invisible wall that dictates system performance, deployment speed, and stability.

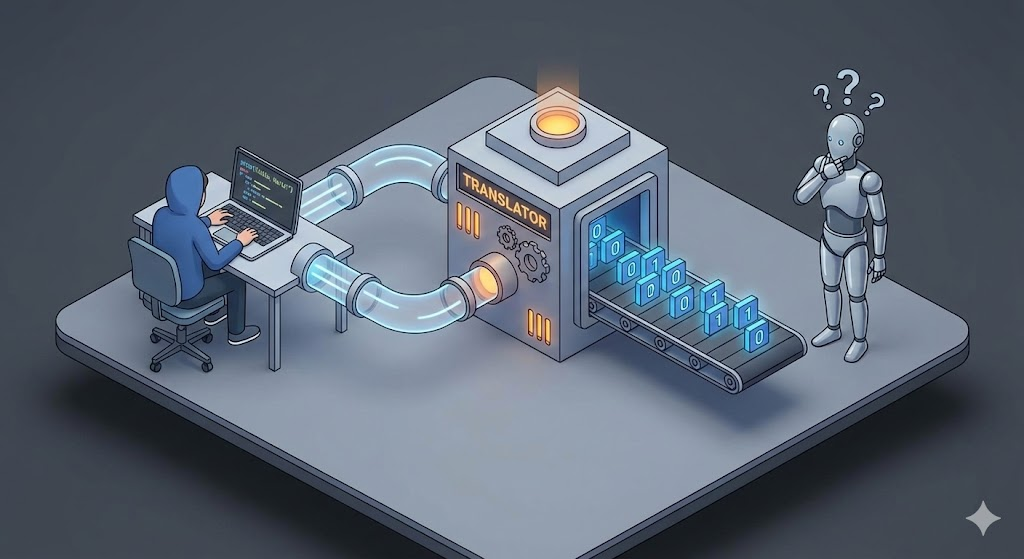

The elegant code I wrote? To the CPU—a brutally efficient but unimaginative worker—it is just alien gibberish.

So, What exactly is a ‘Build’?

What makes ‘Building’ different from simply ‘Saving’?

The source code we write (.java, .c, .go) is, fundamentally, just a ‘text file’. You can open it in Notepad. It is human-readable. But the CPU doesn’t read text; it only understands electrical states: ‘ON (1)’ and ‘OFF (0)’.

A ‘Build’ is the comprehensive packaging process that transforms your human-readable text file into a machine-executable artifact (.exe, .jar, binary).

Think of it like cooking:

- Preprocessing: Chopping the vegetables (removing comments, expanding macros).

- Compilation: Following the recipe to cook the raw ingredients (translating English code into Assembly/Machine code).

- Linking: Plating the dish with sides and sauces (combining multiple object files and libraries into one final executable).

The Bottom Line: Your source code is just the ‘recipe’. The build process is the ‘cooking’. No matter how much you tweak the recipe (code), if you don’t cook it again (re-build), the diners (server) are still eating yesterday’s cold leftovers.

The Digital Fulfillment Center

Let’s visualize the computer internals as a massive ‘Digital Fulfillment Center’.

The ‘CPU’ is the worker on the floor. They are incredibly fast but have zero flexibility. They only read ‘Machine Code (0s and 1s)’—that is their strict instruction manual.

When we write in Java or Python, we are writing instructions in English. The worker doesn’t speak English. We need a translator. How this translation happens defines the ‘personality’ of the language.

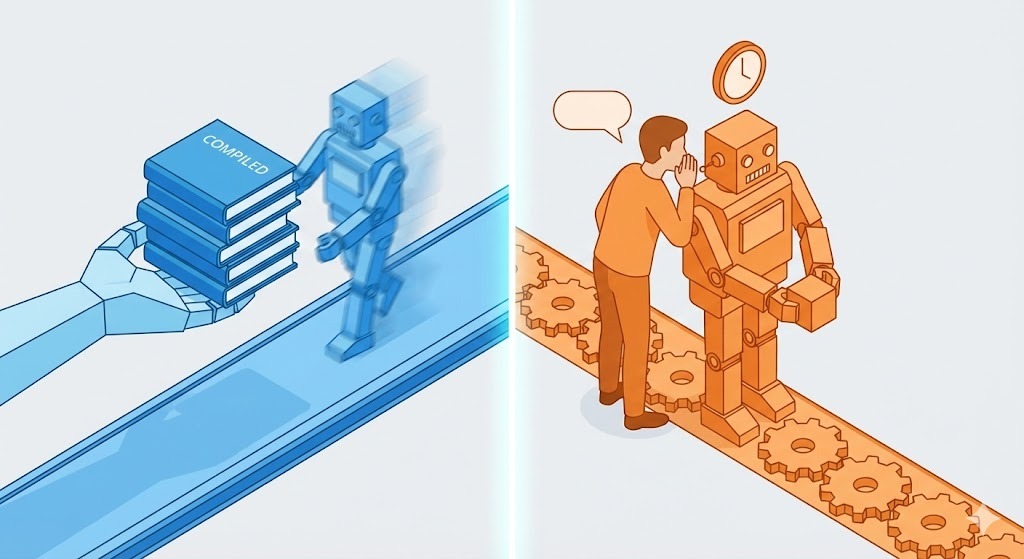

1. The Compiler: The Book Translator

- The Squad: C, C++, Go, Rust, (and Java essentially)

- The Method: Like translating an entire novel from English to Spanish before selling it. The compiler translates ‘all’ the code into machine language (or bytecode) upfront, creating a standalone artifact.

- Pros: The worker (CPU) runs super fast because the translation is already done. It also catches grammar errors (syntax errors) before the book is even printed.

- Cons: If you change one sentence on page 50, you have to reprint the whole book (Re-build).

2. The Interpreter: The Simultaneous Interpreter

- The Squad: Python, JavaScript, Ruby

- The Method: A translator stands right next to the worker, reading the English manual and shouting instructions in machine language line-by-line in real-time.

- Pros: Instant feedback. You change a line, the worker does it immediately. No ‘printing’ required.

- Cons: It is slower because the translator has to think and speak while the worker waits. Also, you won’t know there is a typo on the last page until you actually get there.

[Code Verification] Seeing the Matrix

Talk is cheap. Let’s look under the hood. Is Python really translating things line-by-line? What does the machine actually see?

Python has a built-in module called ‘dis’ (Disassembler) that reveals the bytecode—the intermediate language the Python Virtual Machine (VM) executes.

import dis

def my_function():

a = 10

b = 20

print(a + b)

# Let's peek at the bytecode

print("--- Python Bytecode Verification ---")

dis.dis(my_function)

The Output:

5 0 LOAD_CONST 1 (10)

2 STORE_FAST 0 (a)

6 4 LOAD_CONST 2 (20)

6 STORE_FAST 1 (b)

7 8 LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (print)

10 LOAD_FAST 0 (a)

12 LOAD_FAST 1 (b)

14 BINARY_ADD

16 CALL_FUNCTION 1

18 POP_TOP

20 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

22 RETURN_VALUE

The Breakdown:

- Line 5:

a = 10becameLOAD_CONST(grab the number 10) andSTORE_FAST(save it to slot ‘a’). - Line 7:

print(a + b)triggeredBINARY_ADDandCALL_FUNCTION.

The Realization: This proves Python isn’t speaking directly to the hardware. It is giving commands to a Virtual Machine (the Interpreter), which ‘then’ talks to the CPU. This ‘middleman’ is why Python is generally slower than C, which compiles down to raw assembly instructions like MOV EAX, 10.

The Production Trade-off: What do I choose?

In college, I chose whatever was easiest. I hated C’s segmentation faults; I loved Python’s ‘it just runs’ vibe. But in the professional world, it is always a ‘Trade-off between Stability and Velocity’.

1. The Fear of Runtime Errors (Interpreter’s Weakness)

The scariest thing about running a Python backend is a typo crashing the server at 3:00 AM. Because interpreters translate on the fly, they don’t know that calculate_prie() is a typo for calculate_price() until the code actually runs that specific line. ‘Compiled languages (like Java or Go)’ act like a strict gatekeeper. They refuse to build if there is a typo. This strictness is a lifesaver in large-scale enterprise systems.

2. The Boredom of Build Times (Compiler’s Weakness)

On the flip side, working on a massive Java or C++ monolith can be painful. You change one line of code and stare at the screen for 5 minutes waiting for the build to finish. This is why startups and data scientists love Python and JavaScript. The ‘Feedback Loop’ is incredibly fast. Rapid prototyping often beats raw performance in the early stages.

Closing Thoughts: Theory is Your Weapon

We now understand the mechanics of Build vs Compile. Theoretically, you pick the right tool for the job.

‘But reality is rarely that clean.’ When I joined my current company, the tech stack was already chosen. I was hired as a Java developer, but I found myself debugging Python scripts, fixing JavaScript frontends, and tweaking Android XML configurations.

In that chaos of ‘Full Stack’ expectations, the only thing that saved me was this foundational theory. Syntax changes, frameworks rise and fall, but the way code talks to the hardware remains the same.

In the next post, I will share how I used a deep understanding of one language (Java) to quickly master others, and why understanding the ‘basics’ prevents you from becoming a slave to frameworks.